The Purton Family - from England to Van Diemen’s Land

Earliest branch in Australia

Shadrack Purton (1795-1871)

Another Purton arrives

The next generation of Purtons

Purton myths busted!

Other descendants

Earliest Branch in Australia

The earliest branch of the Harvey Australian family history is on the paternal side, starting with the arrival of Shadrack Purton in Van Diemen’s Land. The Australia forebear of an extensive family in Tasmania and beyond, Shadrack Purton[1] was proud to boast that he had served at Waterloo, so much so that “veteran of Waterloo” was shown when describing Shadrack in his eldest son George’s death notice nearly a century later and it was mentioned in his sixth child William’s obituary. He was not just any soldier at Waterloo, for in that great historical battle he was a private of the 52nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry[2], which some historians believe played pivotal role in winning the battle. Already covered with glory from its campaigning in the Spanish Peninsula, when the 18-year old enlisted in the battalion on the 8th April 1814 it seemed too late for Shadrack to experience battalion triumph. After he joined, it was only few days later that Napoleon[3] surrendered to the European multi-national army (the 6th Coalition) raised against him. But the glory days of the 52nd were not over!

In January 1815, the 1st battalion[4] departed Portsmouth for Cork, where it was due to embark for America, to participate in the final stages of the American War of 1812 - 1815 between the USA and Great Britain[5]. North Sea gales prevented the fleet sailing and by the time conditions had improved, news arrived of Napoleon’s escape from Elba (26th February 1815) and his landing in Antibes on the French Mediterranean Coast with 600 soldiers. There is the famous story of the French Army of Louis XVIII under the command of Marshal Ney confronting Napoleon at Grenoble. The Emperor rode out from his army by himself and challenged the soldiers of France to shot him. The veterans of the French Army switched sides to the shout of “Viva L’Empereur!” – the battle chant as they went to battle to the beat of drummer boys in columns for so many years.

The Congress of Vienna was in the process of redrawing the national boundaries in Europe and it broke up in disarray. The allied armies were re-assembled (the 7th Coalition) under the overall command of Wellington, the hero of the Spanish Peninsula Campaign. The 1/52nd were sent to Belgium. The new recruits, including Shadrack, joined the 7,000 veterans of the Peninsula War and, at Waterloo they again battled ‘le petit corporal.’

The 52nd was under the command of Colonel John Colborne, and was assigned to Lt General Hill’s II Corps, as part of the 2nd Division’s 3rd Brigade under General Adam. Shadrack was a private in Captain John Shiddin’s Company, 1st Battalion when “no instance of a single battalion so influenced the result of a great battle as Waterloo (18th June 1815) was influenced by the attack by the 52nd on the (French) Imperial Guards.”[6]

Following is an account of the decisive action in the Battle,

describing the role of the 52nd. In the battle it suffered

38 killed and 168 wounded. This battle was celebrated for most of

the 19th century, much as we Australians have celebrated

Gallipoli in the 20th century and beyond.

“The Guard marched up to La Haye Sante for the attack. There Napoleon stood aside and left the command to Ney. Ney led the five battalions up the left hand side of the Brussels road. As they climbed the ridge they came under fire from a curve of batteries assembled to meet them. A deserting French cavalry officer had warned of the Guard’s advance.

The Battle of Waterloo at 8pm: The guard attack the Allied line in the closing stages of the battle. The Prussian attack is pressing hard from the East.

The Middle Guard threw back the British battalions of Halkett’s Brigade but was assaulted by the Belgian and Dutch troops of General Chassé and Colonel Detmers who drove them back down the hill.

Major-General Frederick Adams' brigade, which had been sheltered a little to the rear from the artillery, had been brought directly into the line. The attacking Guards came up in such a way that Adams' brigade, the 52nd, was on the French left. The regiment's commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Colborne, watched the charge. He had a plan. It was daring. It could only be executed with great risk not only to his troops but to his whole military career. Fighting in Spain, he had gained a reputation for innovation, but he had done nothing compared with what he planed now. On his left was the British Guard. It appeared that they would take the main attack. If he could wheel his regiment outside the line he would be able to fire directly on the nearest flank of the Old Guard. The destructive fire coming from the British troops directly to the front of the advancing French, coupled with the flanking fire from the wheeling 52nd, would be sure to destroy the charging enemy. First he would wheel the left company of the 52nd to its direct left. It would swing as a gate opens and then stand on the flank of the advancing troops. The movement had to be precise. Any disorder at all and there could easily be a huge gap opened for the French to plunge through. All they have to do was just veer a little more to their left.

Figure 1 - The battle plan of the last action

Colborne explained his orders to his Lieutenants. It was about time to act. The Guard was approaching through heavy smoke. Colborne yelled out his command. The left company pivoted with drill-field precision. The rest of the regiment began to form up on the front company. Colborne had no orders for this action. It was entirely his battle decision. Adams, the brigade commander, rode up quickly and asked what Colborne was doing. Over the roar of musketry Colborne pointed to the French and yelled "To make that column feel our fire". Adams approved of the manoeuvre so completely that he dashed off to bring up another regiment to support. Through the smoke the vanguard of the advancing French had almost reached the top of the ridge. And then suddenly on their flank they saw the 52nd regiment. The shock of seeing their flank imperilled shook the whole column. For a moment the Guard froze. But second later the Imperial Guard recovered. It wheeled some of its troops around and opened a heavy fire against Colborne's regiment. Colborne retaliated with a murderous volley. Other regiments, other units including part of the 95th regiment and the 71st regiment had been brought up in support. They threw in volley after volley[7]. Colborne's manoeuvre must be shattering or it would fail. He screamed "Charge, charge!" and the 52nd flew at the Guard with their bayonets.”

The Battles of Waterloo (land) and Trafalgar (sea) were historical events that defined the beginning of Great Britain being the super power of the 19th century. The British Navy ruled the oceans until World War 1. The Army maintained colonial power in Africa, Australasia, the Indian subcontinent and Asia on which the Empire’s wealth was based. Shadrach’s participation on Waterloo in the action that some historians say was the defining moment of the battle was celebrated throughout his life and beyond by proud Englishmen throughout the world. Being a soldier at Waterloo in the 19th century meant society held you in the esteem that veterans of Gallipoli were held in Australia after WW1.

Shadrack Purton (1795-1871)

Shadrack enlisted in the 52nd at Windsor in 1814. Prior to his army service he seems to have lived most of his life in Kent. Recruits to lower ranks of the English army of the time were either criminals (even escaping capital punishment), destitute or drunkards[8]. Why Shadrack joined is not known but given the way he lived his later life the reason was most probably poverty. Shadrack’s widow sated that they had both been born in Yalding but his enlistment papers[9] name Bishopstone, Sussex, as his birthplace, and his army discharge document sates he was born in the parish of Great Peckham, near Maidstone, where his baptism is recorded in the register of the old church[10].

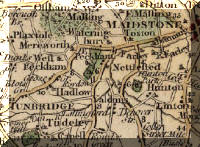

Figure 2 Section of John Cary’s (engraver)) 1787 map of Kent

showing Peckham, Farley and Yalding

Shadrack was born on 15th September 1795 and his name spelt SHADRACH, as in the Bible, and his father’s name spelt PURTON. His parents, Robert and Mary, were described as “travellers[11],” probably driving the wagons that carried freight loads over the new pike roads, as carters were entitled to travel freely between parishes and not suffer the penalties accorded to “strays”, or itinerant workers.

None of the family seems to have settled at Yalding until the 1820s, but in the 1841 England census three of Shadrack’s brothers and their children was living in or near the town, and today there are Purtons still living in Yalding and nearby[12]. In their marriage record, Shadrack’s parents were named as Robert Pirton and Mary Pitchett - married by banns, at Capel Dorking in Surrey. Their first son was named George Purton in the baptism register in the parish of Dorking The other baptisms of their children are recorded villages in the three neighbouring counties of Surrey, Kent and Sussex, confirming that Robert and Mary travelled the ancient roads of Southern England. Robert’s place of death is unknown[13] but Mary’s death and burial in 1808 has been found in the parish record that covers Tudely and Capell (see Figure 1).

Evidence of Shadrack’s siblings is in various church and settlement records. George, James, John and William, were named when Sarah (Shadrack’s wife) dictated an affidavit many years after Shadrack had died, but she probably did not know of younger siblings Samuel or Charlotte. By the 1841 and 1851 censuses the brothers had settled in Kent in rural occupations. James seems to have had no children. In 1851 he was a gardener, working for John Twisden at Bradbourne House, East Malling, where his wife, Elizabeth [Fry] was also a servant[14]. They had witnessed the marriage in 1830 of Thomas Fry. Elizabeth died before the 1861 census, but James was living with Thomas at East Farley where he died in 1864[15]. Burial records show that he was buried with Elizabeth at East Malling.

After the Battle of Waterloo, Shadrack served in garrisons in France (the 52nd was the last English battalion to leave France in 1818), on the Isle of Man and in Ireland[16]. He probably did not marry until he was in Saint John, New Brunswick Province, Canada, near the border of the USA state of Maine where his first child, named George Smith Purton, was be born[17]. The affidavit from his widow, born Sarah Smith, said that they were married in “St John’s Church 1822”, but it was not until 1823 that the regiment went to New Brunswick and there was no church at the army base but there may have been a St John Church in the town (there is a historical church currently standing that was built after Shadrack left St John), but no doubt the regimental chaplain could have married the couple.

In spite of what Sarah later claimed, Shadrack never learned to read and write. His sons George and James may have attended the garrison school on their arrival in Tasmania, but the younger children must not have attended school as they made their mark on marriage records when it was time to sign, as their father did when he signed as a witness to the marriages.

Sarah’s origins are more of a mystery. She may have been with another soldier before she and Shadrack married, and already with the regiment when it went to New Brunswick[18]. Her given age suggests a birth about the end of the century, and if she was born “in Yalding” she may have been the illegitimate daughter of another Sarah Smith, there being a baptism in the register of the nearby village of West Malling, 21 December 1798. Sarah had no records to confirm dates (she claimed that papers had been lost in a shipwreck). The Tasmanian Pioneer Archives[19] misleadingly gives a marriage date of 1833, when their first Tasmanian born son was christened – but their first son was born nearly ten years before this event, and even if it was only in “common law” terms, Shadrack and Sarah had been man and wife for many years before they arrived in Van Diemen’s Land.

Shadrack applied for his discharge in New Brunswick (the 52nd did not leave Canada until 1831), returning to England in 1825 and was posted to the army in Brighton before it was confirmed (12 December 1826). The discharge certificate was duly endorsed at Horse Guards, the office of the Army’s Commander in Chief. His discharge was ‘on account of a hernia occasioned by jumping over a ditch in Ireland”.

The certificate would be used many times as an identification and testimonial. It was also used as an authority for the spelling of his name, as the loop of the ‘h’ looks very like a ‘k’, and this is how it would usually be copied[20].

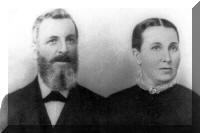

The discharge certificate gives the veteran’s description, “about 31 years of age, five feet ten and three quarter inches in height, light brown hair, grey eyes, fair complexion.” Shadrack was remembered later in life for his upright stance. Picture 3, shows him to be a fine looking man.

After his discharge Shadrack became an agricultural labourer, working with his brothers in Kent. A second son James, was born soon after his discharge, and probably named after his brother, as George had been named after Shadrack’s oldest brother. The third son Shadrach was born in England in 1830 while the family was living with Shadrack’s brother James. Shadrach’s spelling of his name, as recorded in the baptism registrar was the most consistent over time. Shadrach was baptised in James’ parish church in East Farley. Shadrack would have worked where he could, but there was great poverty in the southern counties, his hernia precluded heavy work. Jobs were becoming scarce for even fit men. He would have been an ideal candidate for one of the several emigration schemes that were being mooted.[21] All soldiers of the time had a trade, and although Shadrack’s is described as an agricultural labourer he was no doubt good with horses and expert at driving a carter’s wagon - although the loads would have been too much for a man with a hernia to lift.

In 1831 he was recruited as a servant of the scheme which was later to be named the Cressy Establishment[22]. One of the directors, Colonel Peter Augustus Lautour, who had served with the dragoons at Waterloo, would give his name (as Latour) to part of the Cressy estate which later became the town of Longford. Lautour never came to Tasmania, or to Western Australia where he was associated with an abortive attempt to settle on land around the Swan River, before James Stirling made the first successful settlement. This and other schemes also interested the Wakefield’s. When the Persian arrived with Shadrack, Sarah and their three sons, it was noted that among the passengers were “several persons of Col. Latour’s[sic] Establishment”. Possibly those people were under the direction of Felix Wakefield (a younger brother of Edward Gibbon) on board with his French wife Marie and their small daughter.

Family stories maintain that Shadrack had gone to Van Diemen’s Land with the promise of a land grant in return for surrendering part of his pension. Ex-soldiers were being settled on the land in the Canadian Province of Ontario[23], but it was not until March 1835 that he tried (unsuccessfully) to be granted land, when a colonial settlement scheme was set up for ex-soldiers, and he was already on the Adelphi Estate.

An account of the Cressy Establishment (or to give it its full title The New South Wales & Van Diemens Land Establishment) appears in a volume Old Sheep for New Pastures, author Ivan HEAZLEWOOD. In 1826, Jocelyn Thomas was the Colonial Treasurer, and he was able to arrange for his brother Bartholomew to be given a grant of 20,000 acres and the monopoly on the import of horses. With a small group of friends Thomas[24] formed the company to introduce stud animals into the colony. The 320 ton Albion, which brought out the first consignment of livestock, also brought skilled agricultural workers, and farm machinery. Besides draught and carriage horses, there were Shorthorn and Hereford cattle, and Merino, Leicester and Southdown sheep, the latter being the foundation stock of the breed in Australia. Not surprising the losses in what must have been an overloaded ark were heavy, but a year later when Captain Thomas came out to see his establishment, he could write to the Colonial Secretary that they “had fulfilled to the letter our first proposition by bringing out… three distinct breeds of stock”.

Thomas didn’t stay, moving off to his own property, leaving the care of the settlement in the hands of managers who proved incompetent. By the time the Persian arrived there was no money, and the passengers must have been thankful that their army experience and contacts found them employment.

The Persian had left England 26 December 1831, to a bad start - with its master, Captain Plunket, dying when they were only a few days out. But the aptly named Captain Friend who replaced him gave the passengers a happy voyage - comfortable enough for the times, and particularly so for those who had known the discomforts of army transport. The voyage ended at Hobart the following April. Another passenger would later write of knowing the Purton family since their days together on the Persian, and of the foresight of Sarah who was able to help with welcome tea supplies from her own stock when that of the Cabin passengers ran out. Felix Wakefield’s wife was expecting her second child, and before they arrived Sarah was expecting her fourth. In spite of the barriers between Cabin and Steerage (and the classes they represented) the younger woman would have looked to the older women for help and comfort, and possibly Sarah would give occasional care to Marie Wakefield’s little daughter, no doubt a very different charge from her sons. Wakefield, a former military engineer, was appointed by the Government as Superintendent of Roads. Shadrack was made overseer of the working party building the stone bridge at the strategic town of Ross. Overseers were usually former convicts, but a historian writing of the building of the famous bridge commented on the fact that this overseer was a free settler. A report by Benjamin Horne of an incident involving Shadrack was made as follows:

Chiswick

22 May 1834

Sir,

I have the honor to inform you that Robert Butler 1659 per Elizabeth attached to the gang working at Ross Bridge has been convicted before me of gross insubordination and insolence to Mr. Ch's. Atkinson his Superintendent and to his overseer S. Purton[25]., the latter of whom was violently assaulted and received divers cuts and bruises upon his face accompanied with repeated threats against the life of himself and children should he the prisoner return to the Gang after having been punished.

Shadrack may have owed his appointment to the friendship of Sarah and Marie, although once they were ashore class would have separated them. When Sarah named her first daughter “Amy,” she may have remembered the French word for friend[26].

The two more sons, John, born October 1832, and Robert, born the following year, were christened at Ross by R.C. Drought, the convict chaplain of Green Ponds[27]. By the time William was born in 1836[28] Shadrack had taken up a more congenial post supervising convicts assigned to a Mrs Burt on the Adelphi Estate not far from the Cressy estate. William and Amy were christened together two years later, the ceremony conducted by William Simpson, the Methodist minister from Launceston. From this time on the family would be linked with the Wesleyan movement in Tasmania, and the next generation would find them mostly Methodists. Edward was born in 1842 and twins Mary and Sarah were born in 1844.

Successive musters, electoral rolls and directories show that Shadrack always lived in the Westbury district. Sarah’s oral memoirs (dictated to her son) recalled “we… went to live with Mrs Burt of the Adelphi… for whom my husband acted as overseer for eight or nine years…[then] rented a farm from Mrs Burt…we lived on it for about ten years… then took a farm from the Rev Samuel Martin called Berrisford [29] VON STEIGLITZ, writing newspaper items as QUIZ, Then and Now in Old Westbury, recalls that Edward, (i.e. Shadrack’s youngest son) would be manager for Samuel Martin’s son Henry Martin. Another reference in the same book names “Shadrach” Purton among a number of Methodists who took up land when it was subdivided[30].

In 1842 Shadrack was granted a carriers’ license. Meanwhile his brother William had arrived in Tasmania, possibly to be employed by him[31]. Reliable evidence of this is in the census held in 1848 which shows the family living at Adelphi[32]. The householder is named as “Shadrack” Purton, and there are three more children. Neither births nor baptisms have been found, but these would be Edward born 1841 and twins Mary and Sarah born 1844[33]. Charles Princeps (named as owner) had acquired the property in 1829, with more than half his 2,800 acres granted on the strength of his investment in livestock. His tenant-farmers would fence the uncleared properties during their first year of occupation to prevent cattle straying. Fourteen people were at the Purton home on the night of the census, including two male convicts.

Although the census names the household as all “Church of England”, the Purtons were Methodists – the first Methodist service had been conducted in the home of another of Princep’s tenants[34].

Shadrack’s success in Van Dieman’s Land was use to support the argument against continuing transportation of convicts as a source of labour and wealth. 0n 1st October 1851 his story was quoted in a letter[35] from Lieut. Governor Sir W Denison to Earl Grey in which Denison was attempting to add facts to the debate (the British Government had promised to cease transportation in 1847, but it continued to do so). He disagreed with the arguments of Lord Lyttleton and Sir William Molesworth that the prosperity of colony relied on continued transportation and the cheap labour of prisoners. Proponents of transportation believed the cost of labour on the estates would escalate with the abolition. To support his argument that the colony would prosper from more ‘free settlers,’ he copied an Abstract of the Return of Small Tenant Farmers in the District of Westbury (September 1851), copied below. Shadrack was a tenant farmer.

From time to time the Purton name appears in official documents, - notably in electoral rolls, and when children married and began their own families. The marriages records show Shadrack’s three oldest boys were married to three sisters, daughters of a Scottish neighbour. George’s marriage to Ellen Hay was followed by James’s marriage to her sister Elizabeth and Shadrach to Marion.

John’s wedding in October 1856 was possibly overshadowed by the death of Mary, their youngest sister, earlier in 1856 of “consumption” or tuberculosis. His bride, Mary Thompson Anderson, was also a Scot like her sisters in law, but when William married in 1857, his wife, Elizabeth Elmer, was the daughter of a couple from Suffolk. Her father was John Elmer, and had also been an indentured servant of the Van Diemen’s Land Company [36] travelling on the same voyage of the Company’s ship, the Forth.[37]

When George Purton wrote of the family success in farming the Beresford property he added that they had given their father stock and furniture. It was probably at this time that Shadrack and Sarah and the youngest children moved to live in the township of Westbury.

The decade of the 1850s would have been a prosperous time for the family, with the two eldest boys able to write it is possible that they could keep in touch by letter with William’s family in Victoria, and (if they could afford the penny post) send news to Shadrack’s brothers in Kent[38]. By the end of the decade George and James would be looking to acquire their own land, and they would see an opportunity in the sub-divisions of the large estates opening up across Bass Strait in Victoria, as the drain of workers to the goldfields made it uneconomic to carry the huge sheep flocks.

Shadrack’s brother William had already made the secondary migration and was in Geelong, but it was near Kyneton, on the other side of Melbourne, that George and James would make their home. The advertisement in the Auction pages[39] confirmed - the brothers announced they were leaving the farm “On the Westbury Highway”, and offered for sale an interesting list of stock and equipment[40]. Both would settle at Kyneton - George as a carrier and James, farming not far from town.

Only one of Shadrack’s 3 daughters would marry. Amy married George Best at the age of 35. Mary died young, and her twin sister Sarah did not marry[41]. Of the other sons, Robert died in 1868, aged 35, and the registration of his death does not mention if there was a wife[42]. The youngest Edward married Sophie Wells in 1866. John continued to farm a block in the Westbury area, and Shadrach farmed land near his Hay in-laws on the Gawler Road, near present-day Ulverstone. William began as a shepherd, but soon was working on the Cheshunt estate near Meander.

Living in household of men, Sarah would be glad to have Amy with her, especially with her daughter Sarah being unable to look after herself. It was not until a year after Shadrack’s death that Amy married. Her husband was the widower, George Best, who had five living children to be cared for. George was the son of a Cressy settler, and had arrived as a boy on the Orelia in 1829. As a neighbour from their Beresford days, possibly George was a particular friend of Amy’s brothers.

Shadrack and Sarah lived to the end of their days in a cottage close to the Westbury Methodist Church – both buildings are still standing, but their grave in the Westbury Cemetery is unmarked.[43]. “Notes by QUIZ” referred to earlier, gives a picture of the family’s achievements. The same articles refer to “D.W. Hay” at Violet Banks, (also an Exton property) during the 1850s, when the families were linked by their children’s marriages. Also mentioned is “a grant to Mr. Princeps called Valmond”, presumably the property which was Shadrack’s lease.

QUIZ (possibly confusing Shadrack with another veteran – or romancing a little) went on to write of his memories of the Waterloo veteran and telling how “his good little wife tramped many weary miles with his regiment [and] carried her child on her back”.

Rather more reliable is his account that “in the early sixties Mr Purton left the Berresford Estate and with his wife, his youngest son, Edward, and two daughters, took up their residence at Westbury. Mr Purton had early in life identified himself with the Methodists, and for a number of years was caretaker of the Westbury Methodist Church. He was certainly a fine old man, tall and straight, and a typical soldier respected and esteemed by all who knew him. His remains are resting in the Westbury Cemetery, also those of his wife.”

Another Purton arrives

Shadrack’s older brother William did immigrate to Australia and that may be the genesis of the convict story (see Purton myth busters). William and his wife Mary arrived in Tasmania in 1837. Possibly Shadrack had sponsored his brother as a bounty settler, or he may have been able to arrange for his landlord (Mrs Burt) to be the sponsor.

William was baptised at East Grinstead in Sussex in 1787, but his marriage to Mary Moore[e] took place in Aylesford, in Kent in 1819. The couple settled in nearby Wormshill, where five children were baptized, and he seems to have followed his father’s occupation of carter. In the hard times of the late 1830s the family were “on the parish.”

Schemes devised at this time encouraged emigration to Van Diemen’s Land to save the parish the expense of keeping a destitute family, and give them a chance to better themselves. William’s voyage to Hobart on the William Metcalfe would prove very different from Shadrack’s voyage, and worse than many of the convict voyages. A fellow passenger, Samuel Elliott, recorded in his diary the details of the appalling voyage that brought William, Mary and the five children to the Antipodes. One of the deaths on board was William and Mary’s 2 year-old daughter[44] and Mary herself was lucky to survive as she was probably breast-feeding her fifth child.

An enquiry into the circumstances of emigrant selection followed the Colonial Secretary’s complaint that the potential settlers were unsuitable…unable to “support themselves, much less their children [example] William Purton although entered as aged 45 is ascertained to be nearly 60 the mother rated 36 is nearly 50.”[45] In spite of the belief that the parish had falsified their ages, baptisms confirm the ages as approximately correct. Far from being incapable, once he had recovered from the privations of the voyage William would be able to follow his calling for many years - buying a passage to Geelong in 1839 where he was able to set up his own business, which was carried on by the next generation. Mary would have yet another child in Australia, unlikely for a woman of 50, but not unusual for one in her late 30s. The family would prosper in the new land and hard times would not be known to their descendants. That the cousins were in touch is proved by the joint application made after both fathers had died when they believed that an inheritance was due to them.

One daughter stayed in Tasmania when they moved, married to Peter Sinclair, who was involved as the family tried to find “a pot of gold”. William and Mary’s other daughters had gone to Geelong with them, and married there, but no trace of their sons have been found. In Geelong, Eleanor married timber merchant John Gray (known by the alias “James Steele” and reputed to be an ex-convict) and Mary Ann married John Herbert, a carter like his father in law.

The Next Generation of Purtons

In all Shadrack and Sarah are known to have had eleven children and there would soon be many grandchildren. George and Ellen’s four were joined by ten sisters and brothers after his second marriage. James and Elizabeth would have thirteen children. Shadrach and Marion had fifteen, but they would lose their first two as babies at birth and the next child at less than a year. John’s eleven was a comparatively small family alongside the nineteen born to William and Elizabeth[46] plus the three daughters born to his second wife.

Amy added five to George Best’s family. Edward’s only daughter did not lack for cousins even if she had no siblings. Unmarried, Sarah lived until 1911, no doubt cared for by her sisters in law. A letter refers to her in about 1906, suggesting she was never able to look after herself.

Shadrack’s descendents repeated the familiar names through several generations, with variations. Future generations would argue as to what was the correct spelling of their ancestor’s name. In the 20th century the name has even appeared as “Chadwick.”

George Smith Purton followed the tradition of including their mother’s maiden name, producing e.g. “Helen Hay Purton and “George Ross Purton.”[47] He was the first of the family to marry, 19th June 1850 at the Church of St Andrews, Carrick, he married Helen Wallace Hay (more often named as “Ellen”) daughter of their near neighbour, David Wallace Hay. The witnesses were his new father-in-law and his brother James. The marriage was conducted by Thomas Reiby, and both George and his 17 year old bride signed their names. Six months later the same group would assemble for the marriage of James and Elizabeth Hay, this time the witnesses were David Hay and George Purton. Three years later, when Shadrach married Marion Hay both fathers were the witnesses, David signed his name and Shadrack made his mark.

David Wallace Hay was a carpenter and builder, who had migrated from Scotland with his wife, Helena [Davidson], on the VDL Company’s vessel the Forth about the same time as the Persian arrived at Hobart with the Purton family, but the Company failed to honour its promise of employment and he set off to the court at Launceston, to obtain redress - his overland journey is graphically described in his obituary.[48] On arrival he found that the only lawyer had been engaged by the Company. The doughty Scotsman had some funds of his own, and so was able to charter a vessel and with others similarly placed collected his wife and set off for Hobart where he had no problems in finding employment.

Although his obituary would say that it was after an unsuccessful attempt at gold prospecting David Hay took up the property named Violet Banks, it was many years before the gold discoveries of the early 1850s.`

George, James and Shadrach moved on to a property that was part of the Exton Estate known as Hill Top when Shadrack moved into Westbury. After a number of years farming the property, George went to Victoria, before the sale of 1857, leaving James on their shared property, with Shadrach established at Gawler. Ellen died in Victoria, 15 Nov 1855, leaving three daughters, and one son, John Hay Purton (baptised 6 Feb 1855). Marion seems to have sublimated her maternal instincts in caring for her sister’s children. George remarried (10 Mar 1858) and his second wife Naomi was the daughter of George Ross and Matilda Wathan of Launceston. They had many children who spread the family name throughout Victoria. His obituary tells of his farming “on the Coliban [River]”, but it was as a “railway and general carrier” and timber merchant that he would be better known in the district the business was continued by three of his sons after his death. His obituary names his surviving children, seven sons and five daughters, but many had already moved away from the district in a chain migration that would see Purtons as far away as Swan River remembering the family origins..[49] George had another brush with history – as a promoter of medicine. In the NZ Evening Post - 5 Sept 1903 with heading Could Scarcely Walk Mr G.S. Purton, a resident of Kyneton, Victoria, Australia, state- "Some time ago I was attacked with severe pains and stiffness in my legs, which affected me so that I could scarcely walk when I was recommended to try a bottle of Chamberlain's Pain Balm by our local chemist, Mr.Stredwick...." for sale everywhere 1s. 6d.

“QUIZ” was an old man when he wrote his memories of the early Methodist families[50] of the Westbury district and spoke of Shadrack’s sons and daughters as they were in the 1850’ies and 1860’ies. George Smith Purton, was named as the first superintendent of the Exton Methodist Sunday School, – the Exton Church opened in 1857. Methodists were usually total abstainers, and George’s, funeral service in Kyneton was conducted by the Rev. S.M. Potter of the Temperance League. In a fine tribute[51] the write referred to him as a man who “never sought any public position, but led a quiet, useful, honourable life [his] kindly characteristics won him a large number of friends - all who ever knew him found him as true as steel, a sincere Christian, a faithful friend, and an honest citizen whose word was his bond.”

James continue to farm after his brother commenced his carrying business (his obituary refers to his having farmed in the Kyneton district for 18 years) but he must have been retired to town for several years before his death at his home in Jennings Street. The records have less to say about James than his older brother. Born after the family returned to England from New Brunswick, he would have remembered the voyage to Van Diemen’s Land, and the first few years in the Colony when his father was overseer of the bridge-building convicts at Ross where he and George probably attended school. James and Elizabeth had 13 children in all, and only Lucy (born 1857 died 1860) did not live to a good age. James died 10 years before his older brother, 4 July 1900. Elizabeth lived on until 1916. Both are buried in the Kyneton Cemetery.

Shadrach, the third brother, was also a much respected figure, especially in his church. His obituary refers to the Rechabite ritual at his funeral, implying that he also was a teetotaller. When he died he had been farming for many years in the area described as the North-West Coast, on the Gawler Road near Ulverstone, and area which would be associated with the Purton name in subsequent years. His property Blackberry Hill was left to his unmarried son and daughter[52], their family hospitality remembered for generations.

Shadrach’s marriage to Marion Hay in 1854 completed the trilogy of brother-sister marriages. Marion was much loved by her sisters and by their children, and her memory is kept alive by the “Marion bracelet” handed down to her namesakes[53]. She was unlucky with her own babies. Three died at birth or in their first year before Helen Hay Purton, named for her deceased older sister, was successfully reared. When her sister Ellen (George’s first wife) died soon after the birth of their third child, the motherless baby,[54] christened John, was taken in and raised by Shadrach and Marion. Later they had several girls and eventually a son, also named John, but it was the adopted son John who seems to have inherited from his uncle, with the inevitable friction to follow. Marion’s own son, named John David Hay Purton was not born until 1862 when his cousin John was seven, and probably already helping Uncle Shadrach around the farm. Shadrach died at Gawler on the 4th May 1910[55], but Marion lived well into her 90s. When she died in 1931 it was exactly a hundred years after her parents and those of her husband had set sail for the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. Shadrach’s line is represented in New Zealand by the descendants of John David Hay Purton who settled on the West Coast, changing his name to John Joseph Purton.

William, the sixth son and the Purton antecedent in the Harvey family tree, was born in 1836 in Bracknell, the year that the long delayed bridge at Ross was completed.[56] It seems more than coincidence that it was the year that Shadrack’s brother was selected as a ‘bounty’ emigrant that his name was given to the new baby. William Purton married Elizabeth Elmer on 7th August 1857 in Deloraine. Elizabeth was born 9th November 1840.

Records show that William Purton, was employed by the Archer and Bowman families on the “Cheshunt[57]” estate which is located at Meander, inland from Deloraine. William worked on the estate for 40 years, starting as a shepherd, blacksmithing and assisting the Farm Manager. The estate grew from 6,000 acres to 15,000 acres. The property was irrigated by many hand dug ditches. The estate was eventually broken up into smaller allotments by the Government circa 1907. William told the story that Cheshunt had a tower built and that he would periodically stand in the tower with a telescope watching the workman around the estate, ensuring they were not idle.

Phyllis Ingamells, a great granddaughter, on a bus touring in and around the area visited Cheshunt and saw the cottage on the estate occupied by William and Elizabeth where all their children were born. It’s believed that as they grew, all the children were employed on the estate. Today there are Elmer’s and Purton’s throughout the Deloraine area.

His wife, Elizabeth Elmer was also from a large family.

William and Elizabeth had a large family - seventeen living

children:

|

Name |

Born |

Comments |

|

Rosetta Mary[58] |

1st March 1858 27 March 1938, Kempton |

Married William Henry Slater, 1877, Deloraine, 4 children |

|

William John |

2nd October 1859 8 May 1941, Ulverstone |

Married Esther Close Aug 1881; 8 children |

|

Alfred Henry Phillip |

17th October 1861 |

Married Annie Elizabeth Leith, 1882, Westbury: 2 children |

|

George Lewis Elmer |

30 September 1863 28 August 1945 |

Married Elizabeth McGregor 18 March 1885; 9 children |

|

Edward Shadrack and Sarah Frances |

29th September 1865 |

Edward died in 1865 |

|

Charles Frederick |

26th May 1867 |

Married Annie Quaile, 1882 Launceston; migrated to NZ in 1903; 7 children |

|

Elizabeth Amelia |

2nd May 1869 7 May 1899 |

Married William Axton 1895, Launceston; 1 child (died at 13 years old) |

|

Martha Annie |

12th June 1872 Abt 1952 |

Married David McGegor (brother of Elizabeth) 1891, Deloraine; 8 children; lived in Toowoomba, Qld |

|

Herbert Daniel |

13th August 1874 8 April 1909 |

Married Clara Hills in Stanley in 1899 |

|

Albert Edward |

19th Feb 1876 Abt 1960 |

Married Adelaide Stammers; 4 children; migrated to NZ |

|

Ethel Esther and Lillias Ruth |

19th January 1879 Ethel: 3 December 1962 Lillias: 30 June 1948 |

Ethel married Robert William Stagg 1899, Deloraine; 7 children Lillias married Charles Thomas Watts 1899 Deloraine; 5 children |

|

Francis John |

7th June 1880 3 April 1953 |

Married Ethel Isabel Hainsworth in 1905, Latrobe; 7 children |

|

Jessie Harriet |

21st January 1884 30 June 1936 |

Married twice; 1 child by first husband; second husband George Perry, married 1911 in Deloraine |

|

Ada Susan |

28th October 1885 8 November 1885 |

|

Elizabeth developed diabetes (probably for child bearing), which had no treatment in the late 19th century. She died 7th Aug 1891 of the disease and is buried in the Deloraine Cemetery. Her headstone is clearly marked with the farewell message she left for husband and children.

William’s children are represented in New Zealand by the lines of two of his sons, Albert Edward and Charles Frederick[59].

Following Elizabeth’s death, the 56 year old William remarried on the 8th June 1892 in Deloraine, to Elizabeth Ann Stagg (christened in 1865, aged 27 at her marriage and died 10 November 1942, Heidelberg, Victoria). William and Elizabeth had three children:

- Ida May, born in 23 April 1893, married Thomas Boyce in 1931, died January 1960;

- Gertrude Amey, born 1894, died 1984; and

- Daphne Clare, born 23 September 1895, died 24 August 1978.

Ethel, William’s 5th daughter by his first wife, married her step mother’s brother Robert in 1899. All in the family!

In the last few years of his life, William worked at the Westfield[60] estate. William died 23rd Oct 1907 in Westbury.

William Purton Obituary Notice

Purton myths busted!

The following are some family myths that have been busted by diligent researchers of the Purton family history.

Was there a convict in the family - William Purton?

Family folklore suggests that when Shadrack left Government service in 1836 it was because one of his brothers was a convict in a road gang at Ross. Whether this is a ‘romantic’ story by one of the ancestors or the local historian QUIZ getting it wrong, the family cannot claim the unique Australian “ancient and honourable pedigree stamp” of having a convict in the family.

There were four convicts named Purton transported to Tasmania:

1. Thomas Purton[61] convicted in Berkshire Assizes, 14th July 1817, occupation a woodman aged 34, transported in July 1818 on the Lord Melville;

2. William Purton convicted in Worcester City 10th March 1821, transported in 1821 on the Malabar;

3. Robert Purton, convicted in Middlesex Assizes 5th July 1831, aged 14, transported 11th August 1832 on the York; and

4. Thomas Purton, convicted in Surrey, and transported on the Minerva in 1838.

Barbara Bolt’s research cannot find any relationship to these people by Shadrack or his English relatives. She has copies of convict records and none of the convicts seem to have been in work gangs at Ross. After his release and living in Victoria, Thomas Purton claimed to have committed a murder back in England - the sergeant of police suggested it was a fiddle so that he would be sent back to England for trial. It had been tried on before!

Myth of the Purton “pot of gold”

Before William (Shadrack’s brother) left for Geelong his eldest daughter, Mansell[62], had married Peter Johnstone Sinclair of Hobart. In 1882 Peter Sinclair wrote to his wife’s cousin, William Purton[63], telling him that he had seen the name of Mr G. PERTON in a list of wills and bequests published in the Illustrated London News. Mr Perton had left a personal estate of £261,000, but his will had only provided for about £60,000 to be distributed “Mrs Sinclair’s father used to say she would be a rich woman some day and mentioned this brother that was rich. My intention is to apply at once….”

A footnote to the letter names the sons of Robert and Mary PERTON[sic] as “John, George, William, James and Shadrack, all born in Yalding in Kent.”

The letter continues that further correspondence would come from his son[64] in Melbourne, but the next letter in the sequence (dated 8 Aug 1882) was a copy of the letter from William’s older brother, George Smith Purton in Kyneton saying his mother also recalled a “rich relative”. The following April, Peter Sinclair again wrote to William asking for further family details, and enclosed the letter he had received from London concerning the claim. The matter was further complicated by the information that the wealthy George Perton, formerly a jeweller in Birmingham, was of illegitimate birth, his natural father being a Mr Thomas PEMBERTON.

Various items of correspondence continued between the two families, with comment about the shared cost of the enterprise, and asserting various facts, many of which are demonstrably false. Throughout, the writers claimed that the correct spelling of the surname was “Perton”. The most significant paper is the affidavit sworn by the elderly Sarah, no doubt her memories prompted by her son and nephew, but providing the framework on which the family story has been built.

Transcript of Sarah’s Affidavit:

“I, Sarah Perton[sic] was married June 1822 at the Church of England St John’s, New Brunswick, America. Shadrack Perton[sic] of HM 52 Reg. My husband at that time had four brothers living in the Parish of Yawling[sic] County of Kent England. Their names were John, William, George and James. We returned to England either in the year 1825 or 1826 and my husband’s brothers were living at Yawling were all married and had families. After our return to England my Husband received his discharge and we left for Tasmania, then known as Van Diemens Land about the year 1829. We landed in Hobart and Colonel Arthur was Governor at the time, who appointed my husband overseer of a road party at work on Ross Bridge. We lived there about three years [about 1832] and then went to live with Mrs Burt of the Adelphi near Westbury for whom my husband acted as overseer for about eight or nine years [about 1841] my husband rented a farm from Mrs Burt and lived on it for about ten years (about 1851) we then took a farm from the Rev Samuel Martin at Westbury. The farm was called Berrisford, where we lived for ten years [about 1861]. My husband then gave up farming and we came to live at Westbury where my husband died about the year 1871. I have lived at Westbury ever since.”

The children were named in the affidavit but Shadrach is incorrectly shown as born in Tasmania, although the date of his baptism is correct.

The account continues “my husband was the youngest of five brothers. My brother in law William Perton came out to Tasmania, and after about two years went to Victoria where I believe he died. A daughter of William Perton married Mr. Sinclair and I believe at the present time lives in Hobart”. Sarah then signed by X her mark, and the document was verified by Edward Fowell, JP, 24th day of July 1882.

Other items of correspondence have been retained by the family, asserting that Shadrack had been unable to correct the original error in the spelling of his name which appeared on his enlistment, although he was aware it should have been “Perton”.

The claim seems to have lapsed for a decade, and was revived in the mid 1890s, the papers about the case include “Notes written by W. M. JENKINS” including a letter (unsigned) stating that the writer’s father-in-law was the next of kin of the deceased “George Perton”. Four years later George Smith Purton wrote his will, devoting a paragraph to the disposal of “all money, land or property from a law suit now pending” adding a note to his own copy

“I also bequeath to my son-in-law, A.STEPHENS[65]], the sum of 100 pounds out of the money from Uncle George’s Estate if same is received on account of the trouble he took in the recovery of same”. Nothing further is known about the suit, which was clearly not sustainable. The story of money in the family has persisted to the present day, and should now be put to rest.

What Sarah’s affidavit does confirm is the names and order of her children, and that the families located in and around Yalding in the 1841 census were kin of Shadrack and William, and it is significant that none of the confirmed family records have the name spelt PERTON, and none of the subsequent generations spelt it that way.

The Purton’s were ‘fallen’ nobility

Early Purton family researchers created a family tree back to 1260, when Sir John de Perton was living as lord of the manor in Perton, in the county of Staffordshire. His ancestor Lord William Perton was granted the manor in 1162 by King Henry II, the first Plantagenet to rule England and subject of film (Lion of Winter) and play (Becket). They faithfully traced the family over time, recording the sale of the manor and its land then titles, the family moving from noble to honourable. By the time the family tree was recording members in the 1830’ies, it was impossible to find any cross reference to Shadrack. The researchers must have been hopeful that some light would throw on a branch that linked Shadrack but this never happened. The faux family tree circulated for many years and is still in the top draw of some family members dreaming of a noble past.

The recent research of Barbara Bolt and Robert Cook has debunked this dream. Noble to traveller!

Shadrack was a non commissioned officer

Family history records that Shadrack had a sword, the weapon of an officer or a sergeant in British Army. Together with the fact that Shadrack sought a land grant in March 1835, the province of the officer class in the colony, some family members speculated that Shadrack held rank in the army. Sarah claimed he was a sergeant in her affidavit. In the obituary notice of his eldest son, George Smith Purton[66] its states George was born “in St John’s, Canada, where his father was a sergeant in the regular military force.”

The sword existed – it was used by Victor Herbert Watts, born 20 July 1907 at La Trobe, died 1961, son of Lillias Watts (nee Purton) when he graduated from Duntroon Military College, but Shadrack was a private for all his 12 years and 256 days in the army. How did he come into possession of the sword? It doesn’t take too much imagination to see Private Purton, possibly in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo, looting a souvenir from the body of a French chasseur[67] officer. Looting the dead enemy (and your own side!) for money, jewellery and other valuables, including swords, was usual. To the victor, the spoils! The fact Shadrack kept the sword is unusual – it was worth money and certainly as a private he would not have worn it.

Victor served both in the Navy and the Army. He rose through the naval ranks until, reaching the rank of Petty Officer, he undertook officer training and transferred to the Army, servicing in artillery regiments.

Unfortunately the sword was stolen from Vic’s house on the day of his funeral, along with his medals and other service memorabilia.

Notes on some other descendants

From the time Shadrack went to Adelphi he and his family seem to have become Methodists, even if they were not so before. Later generations seem to have been Baptists, and in the 20th century more than one branch was attracted to the Salvation Army. A son of Ivy Purton (grand-daughter of Shadrach), Tony Sushams, would be fatally injured when, as a Salvation Army officer, he tried to break up a pub brawl in Wellington, New Zealand. In NZ, Cliff Purton, grandson of William Purton, would in his retirement years would pour considerable energy into fund raising for retirement accommodation and other Salvo activities.

Another of William’s grandsons, Victor Watts, would achieve a military rank in the Australian Army’s permanent forces, and a descendent of George Smith Purton is a retired Air Force officer. During both World Wars several descendants of Shadrack served in the Australian and NZ forces, Fred Purton (son of Charles Frederick Purton and Barbara Bolt’s father) in New Zealand was a private in the first and an officer in the second when he was O/C of the Pacific area postal services.

Many of the family retained an interest in transport, although in the later 19th and 20th centuries it was usually the newer forms of “horse-power” in steam and motor industries. All generations of the family have been great gardeners and many have been farmers.

An unusual claim to fame was for a Purton descendent to be described as “The voice of Chopping”, John Purton of Burnie, was publicity officer for the Axemen’s Association of the North-West Coast and widely known through Press, Radio and “calling” the various chopping events, including the world championships of 1978. Still in the sporting field, boxer Walter Stanley (Whitebait) Purton of New Zealand’s West Coast was NZ flyweight champion 1925-6. Whether it is a mark of sporting prowess or merely to emphasise how many descendents of Shadrack still reside in Tasmania, the name crops up frequently in accounts of sports ranging from bowls to Australian Rules football.

Musically Albert Purton was a distinguished cornet player, as soloist bandsman and with the Strand and other orchestras in Hobart in the 1930s, at the same time that his father’s niece, Rona Jones in New Zealand attained her LTCL for piano and began a career as an accompanist. A great grand-daughter of Shadrack’s brother William was Mancell Kirby who first learned the piano from her mother, but showed such promise that she ultimately earned at diploma at the Melba Conservatorium in 1918. Married in 1923, she taught piano for a number of years, but after a trip to Germany and Russia in 1936/7 she acquired a harpsichord and proceeded to master the instrument, largely being self-taught. For many years she would play for the ABC from a studio in her own home in Melbourne.

[1] The army discharge document, signed in 1826, provided the form of spelling which would have been copied to documents for the first name of the Tasmanian founding father, and that spelling has been used in all Barbara has written about him, although others have used the Biblical form, eg. his name appears as “Shadrach” in the title of Robert Cook’s CD, and in the items about the family in Nick Vine HALL Van Diemans Land Heritage. Subsequent generations produced many variants.

[2] Tasks of the light infantry included advance and rear guard action, flanking protection for armies and forward skirmishing. They were also called upon to form regular line formations during battles, or as part of fortification storming parties. During the Peninsular War, they regarded as the army's elite corps.

[3] Paris was occupied on 31 March 1814 by the Allies. On April 6, 1814, Napoleon abdicated in favour of his son, and when the allies refused to accept this and his generals refused to follow him in an attack on Paris to regain the capital, he made his abdication unconditional on April 11. In the Treaty of Fontainebleau he was exiled to Elba, a small island in the Mediterranean 20 km off the coast of Italy, retaining the title of L’Empereur.

[4] Commanded by a lieutenant colonel , an infantry battalion was composed of ten companies (100 to 200 men) , of which eight were "centre" companies, and two flank companies: one a grenadier (a specialized assault soldier for siege operations).and one a specialist light company. Companies were commanded by captains with lieutenants and ensigns (or subalterns) beneath him. Ideally, a battalion comprised 1000 men (excluding NCOs, musicians and officers). . At Waterloo the 52nd’s strength was 1,130 men.

[5] American War of 1812 – 1815 was fought because England tried to enforce a trading embargo on France. The USA insisted on supporting France by trading and running the English blockade, because the French Republican movement had supported the colonists in the War of Independence. US trading ships were being impounded and sailors killed.

[6] General Sir James Shaw Kennedy

[7] In the Bernard Cornwell “Richard Sharpe” series, the key advantage the English army held over the French army was the ability of the infantry to fire their musket volley faster than the French soldier.

[8] Bernard Cornwell in the Richard Sharpe series often described the foot soldiers of the English Army as such.

[9] Letter from Albert Purton, on23 May 1957, and Oct 1961 stated “discharged to Pension Brighton Sussex” differs from his discharge certificate. The pension was 6p per day.

[10] The Weald of Kent, Surrey and Sussex web site states that East Peckham was also known as Great Peckham. The hilltop church remains, a new church below defines West (or Little) Peckham.

[11] Robert Cook believes they were gypsies, but researcher Clive Mintor wrote in 1990 ‘the traveler was an itinerant agricultural laborer who did not have a tied cottage and moved freely between farms as work became available.’ Other researchers state there was a ‘circuit of a traveling carter’, an occupation that sons Shadrack and William followed at times.

[12] District telephone directory

[13] Robert does not appear in the 1841 England census, the earliest census records available.

[14] Owned by the Twisden family, it’s now a rural research station.

[15] 1814 marriage of James Parton [sic] and Elizabeth Fry, witnesses to 1830 marriage of Thomas Fry (1861 census Thomas Ferry[sic] , James Purton 70 “formerly gardener”).

[16] Discharge Certificate

[17] 11 Jul 1824

[18] All the information would seem to point to Sarah Smith having been with the regiment before she and Shadrack married in St John New Brunswick, probably later than the date given in the above – certainly later than the date she gave in her affidavit which was possibly when she “joined the regiment”. Known as “camp followers”, a limited number of women shipped with the troops, “married” to a member of the regiment and “of good character” – hired to do cooking, mending and laundry, and nurse sick and injured soldiers. If widowed a woman could be left behind, but she could marry another soldier, and was given a month in which to do so – and considering Sarah’s age at the time of marriage this seems likely. An account of the regiment in North America speaks of summer work in the fields, the proceeds given to the “Widows and Orphans” fund.

[19] Colonial Tasmanian Family Links - “date for marriage derived from first identified birth.”

[20] A number of Google records show this spelling with other surnames

[21] Even before the famous Edward Gibbon Wakefield wrote his “Letter from Sydney” promoting such settlement schemes

[22] See article Tasmanian Ancestry vol 20 June 1999 and letter March 2000

[23] Catalogue Reference to Latter Day Saints microfilm film CANADA. Military Settlements

[24] Also a Dragoon officer

[25] Research Douglas Burbury - CSO 1-311-7501- Benjamin Horne re prisoner Butler

[26] Sarah’s dictated memoirs name her as “Emma”.

[27] A wider parish than the town

[28] At “15 Minute’s Forest– near Bracknell” - obit.

[29] See the Affidavit in Myth of the Purton “pot of gold”

[30] QUIZ writing in the 1930s in the same vein. Father or son?

[31] See “Was there a convict in the family – William Purton?”

[32] Adelphi Road is at Whitemore, to the south of Westbury and Hagley

[33] Job born 1838 lived one month. CHICK, Neil ed. Van Diemens.Land Heritage incorrect

[34] “ First Methodist church service at Silito’s Farm” QUIZ

[35] Page 56, Further Correspondence on the Subject of Convict Discipline and Transportation, April 30th, 1852 Parliamentary Papers, Volume 41 ,”Great Britain Parliament House of Commons

[36] The company owned enormous area of northwest Tasmania – not to be confused with the Latour Co.

[37] James HAY, on the Forth a year later was probably David’s brother - both were carpenters

[38] Kent Family History Soc. Journal, vol.9 no11, June 2001 – an account written as a supposed letter from Shadrack to James.

[39] Exton Examiner 1857

[40] See Appendix

[41] Reference in the 1880s speaks of Sarah as a permanent dependent, possibly brain-damaged

[42] Brisbane records show a Robert Purton married Lizzie Keech in 1863

[43] Stone erected for Samuel Purton died at Beaconsfield 1888 marks the site

[44] Variously named as “Maria” (diary) and “Mary Jane” in other records.

[45] AOT Colonial Secretary CSO 5/10, Letter to Home office GO 33/26

[46] Three are buried with their mother in the large plot in the Deloraine Cemetery

[47] Possibly a Scottish tradition

[48] Death of an Old Identity in North West Post 3 May 1892

[49] Stewart and Liz Cox

[50] Pioneering Families Aug 1929

[51] Kyneton Guardian August 1910

[52] Eliza Purton Home for the Aged - The Purton name is commemorated in Tasmania at Ulverstone, in a handsome block of buildings bearing the name of Eliza Purton, wife of John Hay Purton (son of George Smith Purton and his first wife Ellen Hay). After his father remarried John was informally adopted by his double uncle and aunt, Shadrach and Marion. According to her son William, who established the home in her name, Eliza Jennings Pettit had worked for the Hays in Victoria when John Hay married her in 1884, and brought her back to Tasmania, not to live on the property known as Blackberry Hill, that was the home of Shadrach and Marion as is sometimes suggested, but on his own property. John died in 1915 and Eliza outlived her husband for many years, dying 20th August 1961 when she had passed the century. Son William John Davidson Purton, served in the first World War in France and was a prisoner of the Germans for a while. William acquired his own farm at Gawler (as the local newspaper reported at the time the home was opened). In 1936 he acquired another property of 147 acres on Castra Road, and later he purchased the Roland View Estate which he subdivided to finance the establishment of the Home. Situated on a hill at West Ulverstone, the view covers the town and the Leven River estuary, in subsequent years the buildings have been extended to provide a landmark in the district and an asset for the Tasmanian north coast. Although the legend that Blackberry Hill was the property that became the Eliza Purton Home persists, the home of Shadrach and Marion, John’s adoptive parents, was left to their youngest son, Thomas Charles (Charlie) Purton who lived in the old homestead with his youngest sister, Henrietta Esther, known as “Ettie”. For many years the old home was the focus of family gatherings, and although the house has been demolished it survives in many photographs.

[53] Ormond [Purton] Cudden

[54] John Hay Purton seems to have been treated as eldest son, Sarah was probably employed by the Martins and “treated like a daughter” (not adopted by them)

[55] North West Post 10 May 1910

[56] Tasmanian Historical Research Assoc. Papers, vol14

[57] Cheshunt was located near Meander, between Deloraine and the Great Western Tiers. Developed by the Archers, it was bought by the Bowman family in 1873 and is still owned by descendants. There is a grand colonial house on the property, built by William Archer in 1850.

[58] There are only 206 days between William and Elizabeth’s marriage and Rosetta’s birth. There is a strong historical theme of prudish behaviour in the Victorian age but throughout the Harvey family history, marriage and the birth of the first born is often less than 280 days, the usual gestation period. Passionate family!

[59] Barbara Bolt is granddaughter of Charles Frederick Purton.

[60] Westfield Estate still operates today and is just outside of Westbury on the Mersey Valley Road to Exton.

[61] Thomas was further convicted in VDL 1819 the charge being “improper conduct as servant to S.Gordon esq. 50 lashes and 2 months labour in gaol gang."

[62] Her unusual name has been found among other Kent families, but it is interesting to note her baptism is recorded as “Mantle”. In Australia the name has been given to descendents of both sexes, the more usual spelling as in Mancell Kirby 1897-1996, who achieved fame as a pioneer of the harpsichord in Victoria. She studied piano in Europe, but taught herself the harpsichord after she had acquired an instrument

[63] Son of Shadrach

[64] Hugh William Sinclair

[65] Husband of Naomi Rebecca Purton

[66] Kyneton Guardian Tues Aug 9 1910

[67] The name Chasseurs à pied (light infantry) was originally used for infantry units in the French Army recruited from hunters or woodsmen. Recognized for their marksmanship and skirmishing skills, the chasseurs were comparable to the German Jäger or the British light infantry. The Chasseurs à Pied, as the marksmen of the French army, were regarded as elite light companies and regiments